Prologue and Chapter 1 “Doc Tweed”

Irreverence 101, Black Humor 101, and Advanced Black Humor are the three subjects that should headline the leadership courses at the Infantry Officers Basic and Advanced schools at Fort Benning, Georgia.

Building Four at Fort Benning is the home of the infantry school. The dean of the school should import lecturers from the Comedy Club to teach the black humor classes so infantry officers can understand the troops.

Inscribed on the plaque in front of the school underneath the statue are these words, “Follow me. I am the infantry, Queen of Battle.” That should tell the young officer something about his future.

The author’s men were an odd assortment, boys really—twelve-month men really. Their pictures were familiar—the cocked hats and the melancholy grins. They enjoyed talking about girls and home, rumors and cars, the little things mostly.

They enjoyed a good joked most of all. Caught in a time of chattel sacrifice, the regret that anchored their black humor was the baseline for their survival. Slogging through the mud, in and out of the vines, fighting a war that was mindless and discomposed, the author’s men had a duty they could not define: to a smile once remembered.

To a man these grunts would lie even if the truth made a better story.

They fought Vietnam’s war—and it sucked.

It was not “The Vietnam War” as the old men liked to say. With no durable memory of defeat—”The Korean War” wasn’t over—these Eastern old men spent one life and then another playing dominoes in Southeast Asia.

Digger, Dogface, Brownjob, Grunt

A Novel

Gary Prisk

Cougar Creek Press, LLC

P.O. Box 11159 Bainbridge Island, WA 98110

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without written permission from the author.

This book is a work of fiction. The settings are real. Incidents, characters, timelines and names are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Edited by Laurie Rosin

Cover Design by George Foster

Interior Design by William Groetzinger

Copyright© 2009 by Gary Prisk

ISBN 978-0-615-25343-5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2008911339

Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication

Prisk, Gary.

Digger, Dogface, Brownjob, Grunt : a novel / Gary Prisk. — Bainbridge Island, WA: Cougar Creek Press, c2009.

p. ; cm.

ISBN: 978-0-615-25343-5

1. Vietnam War, 1961-1975—Fiction. 2. Soldiers—Fiction. 3. War stories, American. 4.War stories. I. Title.

PS3616.R557 D54 2009

2008911339 813.6–dc22 0905

For Linda, the farm girl I married

For Kimberly, the platoon’s baby girl

For Karl, my son

For the boys from Philadelphia’s

Thomas Edison High

and

For the men I once knew

Prologue

Confusion wasn’t the half of it. AK-47s were chopping the jungle into a tossed salad.

While Charlie took aim at his humping tackle, Lieutenant Edward Hardin ran about learning why El Tees didn’t live very long. With his vitals in hiding and his life a crapshoot, if ever a man was hunting trouble—in Vietnam, in 1967—he damn sure found it.

His father warned him not to expect much from the world.

Instinctively irreverent when tending war’s misfortunes, infantrymen from the Twenty-Fourth Foot in the Transvaal, the Fifth Marines and Seventh Infantry in the Chosin Reservoir, and the 173rd Airborne and Fourth Infantry in Dak To, smiled to mask an altered state of mind.

Lieutenant Edward Hardin was naturally irreverent—a bit of luck he had not foreseen. When Eddie received his deployment orders his father read each word and said, “A dogface needs to know how to eat, dig, shit, and shoot. The rest is just the war.”

Scoffing his best scoff while allowing room to avoid the Major’s left hook, Eddie replied, “Yeah, right. The trick is not shitting on your boots.”

Hardin’s men could eat and shoot, dig and shoot, and shit and shoot, all while screaming for a medic. It’s not that chaos came with these men—it’s just that something did.

They were an odd assortment, boys really—twelve-month men really. Their pictures were familiar—the cocked hats and the melancholy grins.

They enjoyed talking about girls and home, rumors and cars, the little things mostly. They enjoyed a good joke most of all. Caught in a time of chattel sacrifice, the regret that anchored their black humor was the baseline for their survival. Slogging through the mud, in and out of the vines, fighting a war that was mindless, and discomposed, Hardin’s men had a duty they could not define: to a smile once remembered.

Sure enough—Vietnam’s war sucked.

A noble cause, the old men said, blood and bile curdling in a steel pot, a boot standing alone, mist curling over the fractured body of one paratrooper, then racing to the next. Hollow eyes glistened with tears of fatigue and winced at the roar of small-arms fire.

Infantry combat is a deeply personal, scarring experience.

Digger, Dogface, Brownjob, Grunt

An infantryman never comes home, regains a sense of empathy, or falls completely in love. He is but a remnant of the boy you once knew—a shortfused remnant.

Coming alive again requires the friendship of time.

* * *

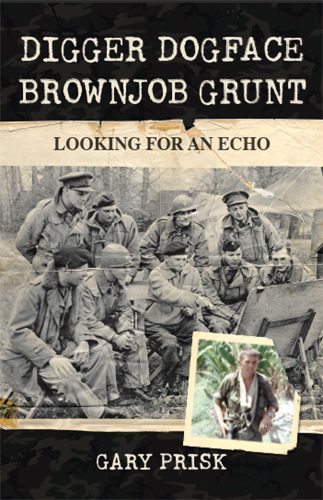

Before I continue, meet my father, Major Edward Hardin. He is the rather lean US Army infantry major standing behind and to the right of Field Marshall Montgomery, the gent seated in the armchair.

These chaps, pictured in Belgium days before the Battle of the Bulge, were the liaison officers charged with tracking the war for Montgomery. Omar Bradley affectionately referred to these combat veterans as Monty’s Walkers.

The Major was a golden glove boxer, enjoying a scholarship to Washington State University. He was devoted to my development, lending me his war relics to play with while I trooped through the woods. I was three years old when he came marching home.

That is when I learned where to find “sympathy” in the dictionary. As if fair warning, the Major died one day in July of 1967. I wish I had known him better, sure enough.

My name is Lieutenant Edward Hardin. El Tee if you like. I fought Vietnam’s war as an infantry platoon leader, primarily against the North Vietnamese Army, the NVA.

I am taping this story for my children, Kimberly and Karl. They will transcribe the tapes and edit the words. But this story is for you. Paint a picture of war while your kids listen.

One more thing—if you’re looking for sympathy, it’s in the dictionary between shit and syphilis. Major Edward Hardin, circa 1946.

Veterans Hospital. American Lake, Washington. July 2001.

Karl sat down. His dad looked better this morning. The old man woke when he felt his son’s weight on the bed.

“Hiya, Pal,” he said, smiling through those crusty eyes. “Lemme get my wits about me for a second and I’ll show you something.” He rolled over and sat up with some effort. He took a long breath before he stood up, then hobbled into the bathroom on bent legs.

“Karl, read those pages on the night table,” he said. “I won’t be a minute.” Karl read. “As grunts go, Edward Hardin…”

The old man came out of the bathroom just as his son finished the third page.

“Recognize that picture? The one next to my desk at home.”

“I never knew that was Montgomery,” Karl said, “but I knew he was important.”

“Your granddad worked for Monty.” He strained to get on the bed. “You bring the tape?” he asked, holding out a paw.

Karl brought out a handheld recorder, loaded with a fresh tape.

“You don’t have to stay here for this. It’ll take a while, and I’ll ramble some too. Your granddad never gave me much about his time in the barrel. A few letters, stories—D-Day and such. And pictures,” he added. “I won’t get it all in,” he said. “Isn’t any paper that’ll put down the sound and the stench. I’ll do what I can, while…” His voice trailed off as he stared out the window, his mouth twisting and working.

“Hell, Karl, you’re no dummy. But we never got to talk about this, really.”

“You never seemed ready to talk about Vietnam,” Karl said, measuring his dad.

“Yeah, I know.”

They sat in the silence of that hospital room, both of them wanting to leave, both of them knowing only one of them would make it. Karl showed his dad how to use the tape.

“Piece-a-cake,” he said, his great hands fumbling with the tiny controls of the machine.

“I’m glad you want to know about that war,” he said. With a sideways glance and the wry grin he liked so well, he gave his son a pat on the back and paused.

“Maybe now I can shoulder my rucksack and drive on in peace.”

CHAPTER ONE

Doc Tweed

B-Med Field Hospital, An Khe Base Camp. 0730 Hours. 4 December 1967.

Hallucinating, Hardin’s voice thickened. He screamed, then laughed. Suddenly quiet, he bared his teeth. Blessed with the silence of a good dog, he cast about, searching for a sandbag to hide behind. With unrelated details running in the same direction, he was stunned by the news of the North Vietnamese Army body count.

Pleased, as if he had won, he fell in with the beauty of his foxhole.

Hardin was sick with a Fever of Unknown Origin. He was having intense and disturbing dreams about his father. And yet, his men kept dying. A pile of bloody bandages exploded. One man turned black, then another. It’s not that these men embraced death; it’s just that they had tired, weathered eyes.

As the war raged on, Hardin’s body was thrown across the ground. He was swimming in mud, suspended in a floating isolation, drifting in a cloudy substance. Strange, glowing images sparked flashes of recall. One, two… nineteen of his men were dead.

Containing the undulating motion was impossible.

Hardin’s heart surged, pushing him through a series of firefights. The fever dragged him in and out of the war. Artillery rounds shattered the trees. He dived between spires of shattered bamboo, scanning a landscape littered with bodies.

Look there, standing alone—a jungle boot.

Hardin’s body ached.

Eight men in Hardin’s infantry platoon were left standing. Could he keep these men alive? The jungle exploded. The carnage was not as confusing as his inability to return fire. Quiet for a moment, he froze. His weapon—where was his weapon? Men appeared and then vanished. Now he was running from foxhole to foxhole, fighting to secure the platoon’s perimeter.

The foxholes were empty.

First Lieutenant Edward Hardin, a stocky, mahogany-faced paratrooper, was a lingering testament to Vietnam’s war, a byproduct of an aching, jungle nausea, trapped in a space without reference. The roar of gunfire was deafening as he fought to slow his breathing.

Trying to release his fear, Hardin laughed.

Doc Tweed

His head cleared in an instant, leaving a jarring pain behind his eyes. The men who littered his dreams now wore blue-green hospital gowns. The jungle screams now came from stubborn hospital carts. The equipment bracketed to his bed had replaced a pile of sandbags.

“Goddamn war,” he said, searching the detail of a nearby face.

Watching the wounded who filled the hospital ward scurry from emotion to emotion, pausing to redirect their energies, Hardin knew they were keen to avoid their own reality. Almost all were relieved: they were going home. Leaning forward, a chill rolled over his body.

Grateful, he stared at the man in the adjoining bed. The man stared back.

A sudden scream caused Hardin to recoil. The wounded man, his head and torso bandaged, his left leg pinned in a cast and suspended in traction, was screaming at his missing hand. Stumped for a moment, the man screamed at his missing leg.

Hardin knew his wounded friend was no longer a wrinkle in Vietnam’s ribbon of endless shit. This man would hear the sound of the explosion again and feel the shock wave fill his body cavities with gas and debris. The concussion will hang in the jungle of this soldier’s mind as though wet burlap, Hardin thought.

Grateful for having all of his digits, Hardin took a deep breath, thinking. Damn, booby traps could vaporize a soldier and leave nary a whisper. It is true that a good grunt is no sudden stew, Hardin mused, but how old could a grunt be?

A tall, thin, rough-looking doctor gave Hardin a nod, offered a gesture of fatigue to the wounded man, and then inserted a needle into his arm. When the wounded man’s high-pitched gabbing turned to a muffled sigh, the doctor stepped toward Hardin, nodding his agreement.

With sweat filling the corner of one eye, Hardin leaned on an elbow, took a deep breath to slow his heart rate, and tried to speak. Before he could muster a word, a black soldier stepped forward, pointing at him. The doctor shook his head.

The rafters began to spin, cycling into a blacker void.

Delirious, Hardin found himself screaming at a tree.

When the tree screamed back, a Viet Cong soldier stood to, centered in a ball of light, his face framed in the mouth of a spider hole. Instantly, Hardin flailed through a tangle of bamboo in a blood-soaked rage. He slit the man’s throat, then slit it again. Suddenly quiet, he was lying in a wet, dank jungle, in Dak To, his four-inch K-bar, dripping with blood.

His father’s voice echoed from the platoon radio, telling him to run.

Frame by frame the paratroopers traced a ridgeline. First Platoon searched the vegetation with a practiced silence, step by step. Breathing was optional.

Digger, Dogface, Brownjob, Grunt

The canopy stood 140 feet. Bits of sunlight pulsed. Leaves fluttered. Shadows changed from dapple-gray to black, then vanished, leaving the eye suspended.

As if synchronized toys, the paratroopers stalked, boots clamored in silence, dancing, searching uphill in a painful display, trapped in history’s gilded funnel. Hardin was afraid. Adrenaline screamed in his ears, drawing him into that familiar sequence of death.

And, as he ran through a vortex of fire, Nuts, the platoon RTO, died.

Hardin watched, shocked for an instant. Nuts’ body jerked violently upward and to the right. His right arm tore into pieces and his M-16 flew into the air. His head exploded, spewing his teeth. His body bounced as AK rounds ripped through his chest.

Frame by frame Hardin was running, screaming, fighting. With a guttural rage he returned fire, dropped his rucksack, looked for cover, reloaded his M- 16, and searched for his enemy in an instant. The vegetation near his head jumped into a boil. AK rounds snapped at his face. And within the confusion, his radio operator lay in pieces and the NVA were gone.

On his knees, wailing, Hardin gathered Nuts into his arms.

Retching at the smell, he turned away, spewing bile. Brushing at his hair, Hardin found the war clinging to his shirt. His friend lay there in the mud, clutching the radio handset, waiting for his El Tee to ask for the radio, his stature growing.

* * *

Hardin came to in a pool of putrid sweat. His bunkmate lay quiet now, drool hanging from his half-smiling mouth. Hardin pushed himself to a dry spot of the bed, listening to the shuffle of slippers on the wood floor and the rhythmic tattoo of a metal walker.

He motioned to a patient and said, “Is there a chart hangin’ on my bed?”

“Right here.” The stranger’s voice had a hard, northern city twang. His bandaged hands held the metal-framed chart as if handling fine china.

“What’s it say?” The stranger glanced at the top sheet trying not to flinch.

With a smirk he looked around the ward and shrugged. After some thought, he said, “Can’t tell. Could be anything.” Then he stepped to the center aisle, pushed a finger into the chart and yelled, “Oh, shit. Here it is. You’re fuckin’ gonna die.” He laughed a roar and threw the chart onto the bed.

That was a good joke, Hardin thought as he looked around the ward. Ward Two of B-Med Field Hospital was a painted version of the average garage. Wood stud walls topped with screens held a rank of open rafters. A large fan mounted in the end wall pulled air through the ward. The white walls sparred with the red-brown dust that coated the rafters and clogged the screens.

Doc Tweed

“Why am I here, Doc?” Hardin’s boorish tone called attention to his newfound awareness. Noticing a bit of mock disgust as the doctor hung the chart on the end of the bed, Hardin shouted, “Tell me a story, ya big shit.”

The chatter on the ward stopped.

The doctor exchanged words with the ceiling lights, angled his head toward Hardin, and stared over his glasses. With an educated tone of voice he said, “You are an FUO, Lieutenant.” His long, bony fingers jabbed the air as he announced each letter. Satisfied, the doctor’s brow joined his heavy glasses in an expression of suspicious searching.

“FUO. Is that what that chart says, Doc?” The surgeon stood into a silent brace. He looked exhausted. “FUO. Sounds like cock-rot. Wait until the bride hears this one.”

Stunned by the texture of a suppressed shout, patients across the ward turned to listen. Some bustled closer, delighted by the sarcasm. As Hardin grew anxious, his head shifted back, and gusts of cold chills ran over his body. When his grin continued, the doctor turned into a tough-guy, grabbing Hardin’s chart and waving it about as if it were Hardin’s balls.

Hardin laughed. “Tweed’s your best shot, Doc—a light brown tweed. Without tweed, no one is gonna buy this shtick you got goin’.”

The surgeon smiled a well-anchored smile and said, “There are strains of malaria and other viruses we cannot identify, Lieutenant.” Watching Doc Tweed rise to his toes, Hardin fancied these opening lines of Tweed’s VD lecture.

“You’ve contracted one of them.”

With a pestering tone, Hardin said, “A light brown tweed with a hint of burgundy.”

Ignoring the jab, Tweed said, “You have a fever of unknown origin: FUO. We’ve been working for days to keep you alive. Ice baths, the whole nine yards.”

“The whole nine yards,” Hardin said. “You docs wrap a viral sludge into a mystery, then blame me for its origin.”

As if being offended was the answer, Doc Tweed massaged his chin with a bony paw, setting his mind to the task. Hardin suspected that FUOs were an integral part of Battle Bullshit, the postulate that the infantry grunt was the origin of unforgiven sin. Every problem a general had was caused by some grunt.

The postulate was fundamentally sound. After all, Hardin had overheated balls, and only a grunt would have such a problem.

With his postulate in hand, Hardin decided to be more aggravating. “Who you tryin’ to shit, Doc? Everything in this dump is of unknown origin. Doctors of unknown origin, DUOs. Dinks of unknown origin. And why the hell’s that black dude hangin’ around here?”

Hardin knew no reasonable man could compete with such all-consuming ignorance.

Digger, Dogface, Brownjob, Grunt

A raucous crowd of wounded men, Hardin’s combat accessories howled, joyously supporting his impertinence with a back-slapping, fist-pounding, holdyour- tools laughter. Doc Tweed shook his head. The hint of a smile crossed his face as he turned and left the ward.

Giving his fans a victory salute to a chorus of “hey, babies” and “dig-its,” Hardin smiled at the thought of pussy of unknown origin, and his head sank through his pillow.

Concentric rings of light narrowed to a tunnel and the stranger, the black stranger, was laughing, conspiring with the tweed-covered surgeon. With a fever ravaged body, Hardin’s thoughts bounced from the Ranger School at Fort Benning to his home on Highlands Road, then mixed the two into his father’s den—only to send him to the slaughter of an NVA ambush.

He was sitting in a Pan American Clipper, behind the right wing: “You are now entering the airspace of the Republic of South Vietnam.” Then he was praying in a dark jungle hollow.

Hardin stood-to in his Special Forces beret, a reserve medic accepting his commission as an infantry lieutenant. His father stood-to in his dress greens, ramrod straight, saluting his Pal. The ceremony turned into the airstrip at Guam. Hundreds of sandbagged parapets formed an eerie display. B-52s lined the runway as far as the eye could see.

“Let’s go home, Pal,” his father said, pulling him away from the plane. “Run, Pal.”

* * *

Number #10, Highlands Road. Bremerton, Washington. September 1950.

The guard was changing along Highlands Road with the lengthening shadows of fall. Muted greens and browns and the whispers of war sparred with the warmth of a bright, sunny day. Highlands Road danced with expectant confusion. Maple leaves, pedal cars, baby strollers, and young parents jammed the sidewalks—fearful of a new war, yet thankful to have a job.

Many a danger lurked along Highlands Road. A youngster could find himself buckled to the rush of a good tongue lashing for running through Aunt Dorothy’s roses. Eddie ran through her roses because she was blocking the sidewalk, and Jimmy Wiggins, a twelve-year-old monster, was chasing him, threatening to pound him into pulp.

Eddie’s dad, the Major, seemed to understand. His mom, the Major’s sweetheart, never understood. Because Aunt Dorothy was her younger sister, Eddie’s mom enjoyed marching him back to the rose bed for a period of public flogging, landscape repair, and whatever remedial training Aunt Dorothy could muster.

Doc Tweed

Of course he was sorry. My God, do you think he enjoyed stomping on her roses?

Eddie stomped on them one day just for the brag.

With a border hospitality Aunt Dorothy could shout “Young man!” and make every dog on the block stop and pee. Eddie learned early on not to stop when she yelled young man. Billy Kirkland stopped once and she twisted his ear until he was on his tiptoes and crying. Then she held on to his ear while she marched him home.

Actually, Billy didn’t march. He bounced on his toes trying to untwist his ear. Not to be denied, Aunt Dorothy would scold him with hideous words.

And that damn Jimmy Wiggins would pound any kid within earshot. Except of course when Eddie’s dad was around. Then Eddie could taunt Wiggins with his best stuff, knowing Wiggins would pound him anyway.

Highlands Road was the best.

Skipping down the sidewalk in front of his house, Eddie tried to miss the maple leaves and the cracks, laughing hilariously at the way his feet seemed to go. Sometimes he would spend the afternoon just to get one clean run to the end of the block. Eddie had to make sure Jimmy Wiggins wasn’t around because if he caught Eddie skipping, Wiggins would tackle him, call him a sissy, and then pound him for fruiting up the neighborhood.

Afternoons in the fall on Highlands Road were devoted to tackle football on the grass field at the bottom of the hill. Player selection was rigged; Eddie played center. If all went well, Eddie would catch a pass in the flat and outrun Wiggins to the end zone. He beat Wiggins to the end zone one day and turned to celebrate. Wiggins tackled him and shoved his face in the mud.

Mornings in the fall on Highlands Road were devoted to getting to school in one piece with your schoolbooks free of mud and your lunch not smashed. The bus stop was on Admiral Perry Avenue, one block south of the intersection with Highlands Road.

Getting to the bus stop was a piece of cake. Keeping your manhood intact while you waited for the bus was impossible. You see, Jimmy Wiggins would wait for Eddie to be less than a man, to fruit up his bus stop, and then he would flog Eddie with cuss words and use Eddie’s books for roller skates. He would belly-laugh when Eddie tried to put his books back together.

One Saturday morning Eddie was boiling along the sidewalk in full stride, sailing over the cracks, when he skipped past the city bus stop on Admiral Perry Avenue. Mrs. Donnager snorted and hollered, “Young man, you better tend to your knitting.”

God, how humiliating. This old bag of gas was one of those neighbors who could accent Eddie’s behavior with agonizing clarity. With a twitch and a grin she could embarrass a young man to the point of not remembering a thing she said. She caught Eddie preparing to pee on a rose bush one day, and scared him so bad he didn’t pee until the shift horn sounded in the shipyard at four-twenty that afternoon.

On Saturday mornings, Mrs. Donnager and Eddie would ride the 9:20 bus to downtown Bremerton. She was on her way to work at the public library and he was on his way to meet his dad. And because he was a gentleman, Mrs. Donnager got on the bus first.

Billy Kirkland had double-dog-dared him to goose the old bag, but Eddie knew the Major would tan his butt if he did.

That didn’t stop Eddie from laughing to himself.

When they got off the bus in front of the public library on Fifth Avenue, the Major would take off his hat, nod at Mrs. Donnager, greet his son with a smile, and say, “How’s my Pal?” The Major would watch Mrs. Donnager unlock the large oak door and post the open sign. Then Eddie would vow to never set foot in the library and take his father’s hand.

Then Eddie would tell his father he was fine, and they would be off, looking both ways and then back to the left.

The Major and Eddie started their Saturdays with a stroll through the farmers’ market, jostling for position to buy the best fruit.

With produce in hand, they turned down Pacific Avenue, heading toward the main gate of the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. Pacific Avenue was lined with fashionable stores, anchored by the post office on the north end and the main gate of the shipyard on the south end.

Bremerton was a lively town in 1950, day and night. Bremerton was a Navy town—a blue-jacket town, its pulse and mood subject to Defense Department work orders and the security measures required to meet those orders. The intersection of Pacific and First Avenues was not a place to fool around. Whispers of war stirred old fears. Ships were arriving for refit. America was restless, and the shipyard bustled with work.

Coming or going, the Marine guards checked workers and visitors. They searched those leaving for contraband or sensitive materials and those entering for cameras or explosives.

First Avenue was choked with girls, pawn shops, lockers, taverns, and a rambunctious sort of life. Sailors and marines thankful for liberty jammed the street corners.

They were full of talk of war.

The Major seemed to know everybody in town, including the strangers. With a firm handclasp, they passed the Greyhound Bus Station heading for the Black Ball Ferry Terminal, next to the YMCA. The Major went to the YMCA for his boxing workout. He would teach you how to box if you listened, and he would just beat the hell out of those who didn’t.

Eddie liked to listen to his dad.

Saturdays ended with a root beer float at the lunch counter in F. W. Woolworth’s Five and Ten Cent Store located at the corner of Pacific and Burwell Avenues, across the street from Bremer’s Department Store. Eddie’s mom sold cosmetics at Bremer’s.

The talk of war today was more heated than on previous Saturdays.

“Dad, do you have to go to Korea?” The Major’s eyes lost some life.

“No, Pal. These sailors and marines are going,” he said, waving down the counter.

The Major died on a Saturday in July of 1967, after a boxing workout on the heavy bag at the YMCA. Major Edward Hardin was worried about his pals.

You see, Eddie’s brother, Court, had just returned from a tour of duty in Vietnam, and Eddie had accepted a commission as an infantry lieutenant and was overdue for orders to go to Vietnam.

The Major was an infantryman in World War II, a Dogface. He landed with the first wave on Omaha Beach in Normandy, on June 6, 1944: D-Day. He knew how war could be. He just forgot to tell his pals. And then he died and forgot to say good-bye.

* * *

Ward Two. B-Med Field Hospital, An Khe Base Camp. 1018 Hours.

The lunch counter at F. W. Woolworth’s and the look in his father’s eye vanished when Hardin’s bunkmate let out a scream and was drawn to the stake, gasping for air.

The surgeon stood-to, tethered to a sottish-looking major. The surgeons huddled near Hardin’s bed, exchanging inferential comments about his behavior, and then Doc Tweed summarized his condition. Hardin smiled to mask a hunch when Tweed rolled a table aside allowing the major to hold a vial up to the light.

The medicine had a viscosity suitable for muster in Aunt Jemima’s kitchen.

“Sir, this is Lieutenant Hardin. FUO. Medevac out of Kontum Province three days ago.” Doc Tweed paused allowing his boss to absorb the input, then adjusted his glasses with a wrinkle of his nose. “He’s been delirious until this morning.” As Doc Tweed’s voice settled into a jellied soup, the major let the glow of his title radiate through the ward.

“Could be a new strain of malaria,” Doc Tweed suggested, prompting his courage.

Hardin mused: the old boys are in heaven, inflamed by cumulative dominance.

“Is this guy a classmate, Doc, or is this a DUO?” The surgeons exchanged confirming nods, then braced into a well-rehearsed conclusion.

“Shut up, Lieutenant,” the major said, showcasing a thick Boston accent. “You’re sick, Lieutenant. You’ve been burning up for days.”

“I knew a girl like that once, rolled on for days.”

“Shut up, Lieutenant. Take this.” He handed Hardin the vial.

Hardin selected a belligerent grin and said, “It’s at ease, Dipstick, not shut up.” Hardin thrust the vial at Tweed. “You take it, Tweed. It’ll cure your constipation.”

At this juncture, the major started a “Let’s reason with the patient” routine, rambling on about casualties, his lack of sleep and pussy, and a persistent cough he had acquired. The old boy glanced at the chart and then at his companion. With an emphatic breath, he said, “This is probably a strain of malaria. Could be a virus. We aren’t sure.”

Tweed stood-to with a skewering look, keeping a parade-ground eye on his boss.

Hardin’s sit-rep was fluid at best. Flashbacks filled with guilt sacked the hospital ward with searing bars of frustration. And if guilt were not enough, Doc Tweed and Major Dipstick were marketing Texaco’s answer to FUOs.

“Look, Major,” Hardin said. “I’m kind of dizzy.” Hardin laid his head on his pillow and the hospital ward slowly tipped over.

* * *

Vietnamese milled around the air base as if they owned the place, jabbering, smiling at the wrong times. Hardin bumped into one man while staring at another man. They looked shifty. “That’s the bus, Lieutenant, the bus to LBJ— Long Binh Junction. The blue bus with mesh on the windows. That’s what it’s called, LBJ.”

“Your overseas trunk will be shipped to An Khe. Your orders were changed, Lieutenant. Well, lemme see. An airborne brigade has invited you to a party they’re having in Dak To.”

“Chopper leaves for An Khe at 1030 hours. Good luck, Lieutenant.”

* * *

The wounded man, his anguish rooted in a blackened self-image, screamed again. Hardin sat straight into a firing position and found Doc Tweed locked in a brace. Tweed’s frown forced his unkempt brow to sit on the bridge of his nose the way moss sits on a rotting log, his eyes a pair of glazed raindrops.

Breathing slowly, Tweed cracked a modest smile. Holding the vial to the light, he then offered Hardin the medicine.

Shaking his head, Hardin said, “I’m gonna split, Doc. I gotta get back to my boys.”

With a grin and a nod Tweed agreed. “You’re my only mystery. The rest are banged, broken, and bruised.” With a matador’s motion Tweed offered Hardin the floor, then said, “Being the smartass that you are, Lieutenant, makes you a sick asshole.”

“Sick asshole,” Hardin said with a worn out huff. “No shit. Now I’m a sick asshole. I don’t mean to jack ya around, Doc. I’m not takin’ that nasty shit.” Tweed’s face fell tired. He set the vial down on the table, searching the contours of the bandaged soldier.

“I want my clothes, Doc. I’m goin’ back to the bush.”

Hardin swung his legs off the bed, hoping the change of altitude and the blood settling in his feet would slow his heart rate. Instantly, his vision cycled into a semidarkness, then back to a harsh cone of light as the restless thump of his heart stabilized.

“Look, Doc.” Hardin hesitated, working for air. “Stick with the AK holes. The wounds you can mend.” Hardin stood, holding on to the edge of the bed.

“I can stop the bleeding, I can’t fix the wounds.” Tweed’s voice carried obvious regret. “The war has consumed any good nature I hoped to have. The amputation rate is high.” Hardin fought to keep pace as they turned down a hallway and into a room lined with plywood cubicles.

“That’s your gear,” Tweed said, apologizing for Hardin’s meager assets. The cubicle was assigned to bed number 218. In the end, the scarred jungle boots, socks, weathered fatigues, and his granddad’s watch, had stood their post alone.

Doc Tweed adjusted the waistband of his pants, then paused, seeming to ward his anxiety and conclude his business: troubled by Hardin’s medical status.

“I’ll make it, Doc. There’s nothin’ to this combat shit.”

Tweed took a pull on his nose, then massaged the air with a modest sigh. Saturated with the butchery, more casualties were inbound, and he could not stop the killing. Shackled to a system designed to produce dead bodies, and charged with impeding the process, Hardin knew Tweed struggled with the contradiction.

Being a Doctor of Unknown Origin was one way to hide from the truth.

Tweed shook his head with a quiet laugh, and said, “Doctors of unknown origin. That’s a great concept.” He shook his head and his eyes registered the humor.

“Understand this, young stud: I want you out of here. Take it easy for a day and you’ll be on your way,” Tweed said, trying to make the liquid swirl.

Hardin pointed at Dipstick’s office. “That med is nasty. Give it to the major.”

Tweed nodded. Indifferent, he turned to leave, then stopped. “You’re going be hurting for a while. If it’s malaria you’ll be back.” Tweed was looking and talking into an empty hallway.

Hardin dressed and shuffled down the hallway of the administrative area. A sign waving in an air-conditioned stream welcomed him to the army field hospital— B-Med.

Curious faces analyzed his progress. Gravity clung to his boots as if wet tar. His feet slapped the floor, jarring his thighs into his balls. Aiming for the front door, Hardin’s vision jumped in and out of focus.

“Where’s the Holding Company?” he asked. The nurse backed away, pointing. Were those real tits? “Holy shit, El Tee, look at those trotters.” He could see clearly now.

“Top of the hill,” she declared with well-seasoned humor.

Hardin’s grin annoyed itself into a stare as he perked her nipples, then coached the tightly wrapped cheeks of her ass as they fought for space.

Admiring his clever nature, he took the front stairs with a rush, clinging to the handrail, allowing gravity to bring each step to meet his foot. By the time he stumbled into the dirt roadway his cock had simmered to a gallop. He needed a shave. His fatigue shirt bore no name or insignia, and his boots were scuffed into red suede.

“How far is the Holding Company?” Hardin asked, pestering a passing GI.

“Half a mile.” The man shook his head. “No hat, no shave. You’re in for some trouble.”

Never quite free of supervision, Hardin plodded on. The walk was drudgery, gallons of sweat spiced with a fever narrowing his vision. Spotting the company guidon and bulletin board, and laughing at the circles of white rocks, he comforted his humping tackle and opened the orderly room door.

“Who the hell are you?” the first sergeant shouted, accelerating around the back corner of his desk, closing on Hardin with a hedge for a body that looked to be one continuous muscle.

“Lieutenant Hardin.” Hardin raised his right hand. His assailant stepped to a halt, fists clinched, wanting to sacrifice this piece of dirt to a sea of other duties.

“You look like hell, Lieutenant. You better get your shit in one bag. Lots of brass around this area.” The old sergeant’s head shook with color as he found his chair.

“Fuckin’ teenage lieutenants.” Top screamed out the back of the tent.

With a short nod, the old sergeant settled into his desk, and after a welltimed pause motioned to his Charge-of-Quarters runner. “Show this officer where he can wash up.”

Hardin followed the CQ runner past the mess tent.

Gesturing to his right, the PFC said, “You can crash in either of these hootches, Lieutenant. Here’s a razor and shaving cream.” Hardin’s run-in with the first sergeant had amused the man.

“Somethin’ funny to you, stud?”

“No, sir. You look a little ragged, that’s all.”

The cold water was oily and smelled of Vietnam. Hardin stared into the small mirror, delicately guiding the razor around the wound on his left cheek. Five weeks before, a spire of elephant grass had sliced his lower jaw, leaving a crescent shaped wound nearly one inch long.

Alerted by the sound of the razor, sweat stung his face as he dabbed at the wound. Stray voices filtered around a sandbag wall. The first sergeant was yelling into his telephone.

Refreshed, Hardin mounted the steps. The old sergeant stared at him with a lumbering disgust. Instantly angry, Hardin grabbed a stack of papers from the desk and sat down.

“Is Second Battalion still in Kontum, Top?”

Top reached across the desk and grabbed the papers, permitting an expression of mistrust. Not to be outdone, Hardin bumped the nameplate from the center of his desk.

Pestered by an indifferent shudder, Top said, “The mail chopper flies to Kontum every morning—0700 hours. Chopper pad’s down this road. Where’s your gear?”

“Kontum, I guess. Blacked out in the bush.”

Top smiled with a confirming nod.

“Chow hall’s that tent, 1730 hours.”

Hardin shuffled across a stretch of wooden-slated duckboards to the first barrack and laid down on a corner bunk. With a chilling strain, he listened to his father’s voice as concentric rings of light converged, centering his vision on the image of an ornate cross. The eight-pointed iron cross, with its dark purple ribbon, lay in an oak case in his father’s den.

* * *

Number #10, Highlands Road. Bremerton, Washington. September 1951.

“This picture is special, shot during one of Monty’s briefings for liaison officers. Eight liaison officers worked for Monty on D-Day. During the European Campaign three liaison officers died. Six of us survived from the original group.” The Major knocked tobacco from his pipe.

“How come you’re wearing a tie, Pops?”

“The Field Marshall insisted on full military dress. The exception was when Winston Churchill paid a visit. I got this cigar wrapper from the Prime Minister when we crossed the Rhine River. His name’s engraved on the seal.” Eddie ran a finger over the cigar wrapper.

“Churchill made quite a show out of pissing in the Rhine River, laughing through cigar smoke about pissing on Germany.” Eddie picked up an oak case from the lamp table near his father’s chair and pushed the glass top aside.

“That’s a Bronze Star, and some campaign battle ribbons. This one is the Victoria Cross. The VC is struck from a cannon the British captured during the Crimean Campaign.”

* * *

Veterans Hospital. American Lake, Washington. 1995.

Karl looked at what he had typed. A British acronym rang in counterpoint from his grandfather’s den, exposing one irony of his father’s war. VC: Victoria Cross or Viet Cong.

What he heard on the tape was not the voice of the father he knew. The language, the jeering cockiness, the words were foreign. How could these have come from this sober and responsible man? True enough, he wasn’t a choirboy. He wasn’t a womanizer or a racist either. Did the war put this in him, or did it take it out?

Even his voice changes as he speaks these words.

“Here,” he said on the tape, “put in here the piece from your grandfather that I wrote out on the top page. That was his war. I don’t think you could talk turds in that war. You can just ‘x’ out those words if you want, or put funny symbols, like they do in the comics.”

“Anyway, after that, go back to the tape. My mind surged…”

* * *

Holding Company Barracks. An Khe Base Camp.

Hardin’s mind surged one moment, then marched with the rhythm of his heart, sorting odd bits of memory, randomly selecting an archive to explore. His body shook suddenly, fighting the involuntary tremor of aching muscles. Images confused: first his father, then his family, then the doctors, mixed with snippets of an NVA ambush, mixed again as if searching for a reason.

Any reason.

Hardin screamed as he removed the rucksack from his radio operator’s body. The ambush destroyed Nuts in the watered blink of an eye, his death joining an accumulating blur.

Meat and bones had splattered across the jungle, coloring Hardin’s face and uniform. The platoon radio lay in pieces. Fish took the radio battery, ammunition, and unit items from Nuts’ rucksack. Squeak put the small personal items in the map pocket of Nuts’ pants. A medic handed a dog tag to Hardin then tied a dog tag into the boot lace on Nuts’ left boot.

The rotor blades of the medevac chopper seemed synchronized with the pulse of the war, as medics scoop body parts into a poncho. Blood flowed from the seams of the poncho: drops suspended in the smoke, then thrown about by the rotor wash. The cabled jungle penetrator drew the litter basket from the clay mud and turned slowly, lifting Nuts through the trees.

Nuts’ casket would be closed, stamped with a leprous labeling—nonviewable.

The ambush lasted fewer than thirty seconds. Nobody saw the enemy, the NVA. Hardin’s war would last another thirty seconds. The next enemy soldier would suffer a slaughtering meant for hogs. Retribution wasn’t killing. Retribution was payback, a responsibility, a moral oath, an obligation, and the purest form of attentive lunacy.

Educated in the woods of the Missouri Breaks, Nuts understood loyalty.