BOOK REVIEW: ‘Eisenhower in War and Peace’:

For Ike the First Biography That Talks Across the Havoc of War

Reviewed by Gary R. Prisk

D-Day’s on. Nothing can stop us now

– Dwight D. Eisenhower

Little can match the age-old romance of cavalry or the pictures that governed my father’s den. In 1952 Eddie Prisk — ‘The Major’ — enlisted my help, escorted me to his 1950 Chevrolet, handed me a bucket filled with ‘I Like Ike’ buttons, and we were off. Assigned ‘every single’ door in the Sheridan Park Naval Housing neighborhood of Bremerton, Washington, a navy blue-jacket town, my orders were clear.

I was relieved when Ike won the election. The Major stood a little taller. His picture with General Eisenhower and Field Marshal Montgomery was moved to gather more light.

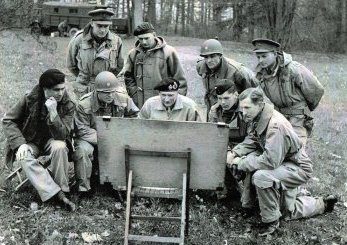

Major Edward ‘Eddie’ Prisk had been a US Army infantry major assigned to the British, and was interviewed and hired by Field Marshal Montgomery to be one of eight personal liaison officers for Monty, and was assigned to 21st Army Group Tactical Headquarters—from Normandy to the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp. Omar Bradley affectionately called these liaison officers ‘Monty’s Walkers’.

As cobwebs want removing, Jean Edward Smith’s “Eisenhower in War and Peace” (Random House, 976 pages, in-text photographs, $40.00) has no unworthy ingredients. Smith’s notes are drawn from storage depositories along Gunwarf Road, in Portsmouth, England, to the personal notes of Kay Summersby. Beautifully written, Smith’s work brings to the art and craft of biography a prose that shows the reader the reason that produced the will that was Eisenhower’s life—warts and all.

As cobwebs want removing, Jean Edward Smith’s “Eisenhower in War and Peace” (Random House, 976 pages, in-text photographs, $40.00) has no unworthy ingredients. Smith’s notes are drawn from storage depositories along Gunwarf Road, in Portsmouth, England, to the personal notes of Kay Summersby. Beautifully written, Smith’s work brings to the art and craft of biography a prose that shows the reader the reason that produced the will that was Eisenhower’s life—warts and all.

Reading Smith’s work has been enjoyable. I will read it again and insert each of the hundreds of notes and quips as I go. The words ring with a proper sense of religious truth. At times I could hear the intensity of Eisenhower’s voice. I could also hear his claims of false fidelity.

Smith details Eisenhower’s military mistakes with clarity, tying Eisenhower’s lack of combat experience to his failed offensive strategy of attacking all-along-the-front, as if the Civil War or the Great War had never occurred. Thousands of men lost their lives in North Africa, on the island of Sicily, at Salerno, and at Anzio because of Eisenhower. And yet, with these battles in his rear-view mirror, Eisenhower took command of the land battle from Montgomery after the Normandy invasion and stopped the Allied advance into the Ruhr—stopped to regroup along an extended front, so he could once again attack all-along-the-front, thus allowing the Germans to regroup. This error brought about the ‘Longest Winter’ with its Bulge and extended the war by six to eight months.

Gary R. Prisk

Smith details Eisenhower’s friendship with General George ‘Georgie’ Patton, America’s favorite cavalryman, with his ivory 45’s and his helmet plume laid flat by the winds of war. Patton’s WWI combat experience was brief however, perhaps a matter of hours, and Smith describes his wound as serious.

Such a wound in Vietnam’s war, no bones, no arteries, no organs, were called ‘Hollywood Wounds’—a pop of morphine and a ticket home. And so it was for Patton. On the way home, fresh from the front, Patton cushioned his recovery ensuring the enlisted man that drug him to safety received a Distinguished Service Cross (DSC), thus ensuring that Georgie himself would receive equal recognition and perhaps more.

And so he did—tradition.

I am impressed by Smith’s generous treatment of Field Marshal Montgomery. Such recognition has been remote all these many years. Monty arrived in Egypt in early August of 1942 to take command of the British 8th Army that had been driven by Rommel’s Afrika Korps across North Africa to Egypt’s door. Even though he was in Egypt in August of 1942, biographers and historians have assigned the failed landings at Dieppe, on the coast of France to his folio.

The first Allied victories were achieved by Monty at Alam Halfa Ridge, and El Alamein in Libya in September of 1942, lighting the fires of optimism and setting the stage for OPERATION TORCH which Eisenhower completely fouled up by splitting his forces, and attacking on three fronts well away from Tunisia, thus leaving Malta exposed.

Smith rightly gives credit to Montgomery for planning the Normandy invasion, altering Eisenhower’s staff proposal from a three-division front to a five-division front, from one landing site to five, and from five follow-on divisions to nine. Montgomery also insisted that a door-hinge be set at the city of Caen thus forcing the Germans to concentrate their forces at Caen, thus allowing Omar Bradley’s troops to swing the door south, then east and then north.

That was the original plan. Bradley knew the plan and so did Eisenhower. Yet the press at the time featured is Monty’s lack of aggression that allowed Germans to escape through the Falaise Gap. Eisenhower said nothing to correct the record.

General Omar Bradley is noted in Smith’s work as one of the ablest of the lot. Major Edward ‘Eddie’ Prisk thought so as well.

Jean Edward Smith’s “Eisenhower in War and Peace” should be short-listed for the most prestigious awards. He showed that Dwight David Eisenhower’s achievements as a soldier and a statesman were wholly consonant with his gifts.

About the reviewer

Gary R. Prisk is a best-selling author and an infantry veteran of Vietnam’s war and the first Gulf War. He began his army service as a Special Forces medic with First Group, attended parachute school at Fort Benning in 1964, received a regular army commission through ROTC at the University of Washington in 1966, fought in Vietnam’s war with the fabled 2ndBattalion of the 503rd Infantry, 173rd Airborne Brigade in 1967 & 68, and became an army Ranger in 1969. Joining army reserves in the Seattle, Washington area Prisk returned to the University of Washington earning degrees in Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, an MBA in Finance, and taught Finance at the university as part of his doctoral studies in finance. Prisk continued his service in the army reserves for 29+ years ending his career as the reserve-component Chief of the Battle Coordination Center for VII Army Corps, headquartered in Stuttgart, Germany. After retiring from the construction industry Prisk began writing and lectures on Vietnam’s war.